|

Arabic Chaldean Hispanic Organization (ACHO)

http://www.acho1.org/

Please support

H. RES. 1725 Bill

501(c)(3) Tax Exempt

| |

|

IRAQI CHRISTIAN FLAGS |

|

|

|

|

|

Assyrian people

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(Redirected from

Assyrians)

|

|

This article needs attention from an

expert on the subject. See the

talk page for details.

WikiProject Assyria may be able to help recruit an expert.

(June 2011) |

Assyrian/Chaldean/Syriac

people

Sūrāyē /

Sūryāyē /

Āṯūrāyē

[1]

|

|

Ashurnasirpal II �

Abgar V of Edessa �

Ephrem the Syrian �

Pope Constantine �

Naum Faiq �

Agha Putrus �

Freydun Atturaya �

Alphonse Mingana �

Ammo Baba �

Rosie Malek Yonan �

Andre Agassi �

Kennedy Bakirciogl� |

| Total population |

| 3.3 million[2]

- 4.2 million (1994)[3] |

| Regions with significant

populations |

|

Middle East |

|

|

Iraq Iraq |

911,987 - 600,000 - 800,000 |

[4][5][6] |

Syria Syria |

877,000 - 1,139,000 |

[7][8] |

Iran Iran |

74,000 � 80,000 |

[9][10] |

Turkey Turkey |

24,000 � 70,000 |

[9][11] |

Lebanon Lebanon |

100,000 |

[12] |

|

Diaspora |

|

|

Sweden Sweden |

100,000 - 120,000 |

[13][14] |

United

States United

States |

100,000 - 490,000 |

[15][9] |

Jordan Jordan |

100,000 - 150,000 |

[16][17] |

Germany Germany |

90,000 |

[18] |

Australia Australia |

24,505 - 60,000 |

[19][20] |

Canada Canada |

38,000 |

[21] |

Russia Russia |

70,000 |

[22] |

Netherlands Netherlands |

20,000 |

[22] |

France France |

20,000 |

[22] |

.svg/22px-Flag_of_Belgium_(civil).svg.png) Belgium Belgium |

15,000 |

[22] |

Switzerland Switzerland |

10,000 |

[22] |

Denmark Denmark |

10,000 |

[22] |

Italy Italy |

3,000 |

[22] |

|

| Languages |

Syriac,

Neo-Aramaic

(also

various Neo-Aramaic dialects)

Arabic,

Persian,

Turkish |

| Religion |

|

|

| Related ethnic groups |

Mhallami

Other

Semitic peoples |

The Assyrian people[23]

(originally and most commonly known as Assyrians and other later

variants of the name, such as; Syriacs, Atorayeh,

Ashuriyun, Assouri, Syriac Christians, Suroye/Suryoye,[24]

Chaldo-Assyrians, (see

names of Syriac Christians)) are a distinct

ethnic group whose origins lie in ancient

Mesopotamia. They are

Eastern Aramaic speaking

Semites who trace their ancestry back to the

Sumero-Akkadian civilisation that emerged in Mesopotamia circa 3500

BC, and in particular to the northern region of the

Akkadian lands, which would become known as

Assyria

by the 23rd Century BC. The Assyrian nation existed as an independent

state, and often a powerful empire, from the 23rd century BC until the

end of the 7th century BC. Today that ancient territory is part of

several nations; Assyria was ruled as an occupied province under the

rule of various empires from the late 7th century BC until the mid 7th

century AD when it was dissolved, and the Assyrian people have gradually

become a minority in their homelands since that time. They are

indigenous to, and have traditionally lived all over

Iraq, north

east Syria,

north west Iran,

and the

Southeastern Anatolia region of

Turkey.[25]

Many have migrated to the

Caucasus,

North America,

Australia and

Europe

during the past century or so. Diaspora and refugee communities are

based in Europe (particularly

Sweden,

Great Britain,

Denmark,

Germany

and France),

North America,

Australia,

New Zealand,

Lebanon,

Armenia,

Georgia,[26]

southern

Russia,

Israel,

Azerbaijan and

Jordan.

Emigration was triggered by such events as the

Assyrian genocide in the wake of the

First World War during the

breakup of the Ottoman Empire, the

Simele massacre in Iraq (1933), the

Islamic revolution in Iran (1979), Arab Nationalist

Baathist policies in

Iraq and

Syria,

the

Al-Anfal Campaign of Saddam Hussein.[27]

and to some degree

Kurdish nationalist policies in northern Iraq.

The major sub-ethnic division is between an

Eastern group ("Assyrian

Church of the East" Assyrian "Chaldean

Christians", "Syriac

Orthodox", and "Ancient

Church of the East") indigenous to

Iraq,

northwest Iran,

northeast

Syria and southeast

Turkey,

and a

Western one ("Syrian

Jacobites").

Most recently the

Iraq

War has displaced the regional Assyrian community, as its people

have faced ethnic and religious persecution at the hands of both

Sunni and

Shia

Islamic extremists and

Arab and

Kurdish

nationalists. Of the one million or more Iraqis reported by the

United Nations to have fled, nearly forty percent (40%) are

Assyrian, although Assyrians comprise only 3% - 5% of the Iraqi

population.[28][29][30]

History

The Assyrian people can trace their ethnic and cultural origins to

the indigenous population of

pre-Islamic and pre-Arab

Mesopotamia (in particular

Sumer,

the

Akkadian Empire,

Assyria,

Babylon,

Mari,

Eshnunna,

Adiabene,

Osroene,

Hatra and

the province of Assyria under

Achaemenid,

Seleucid,

Parthian,

Roman and

Sassanid rule, since before the time of the

Akkadian Empire.

Mesopotamia was originally dominated by the

Sumerians (from 3500 BC) and the native

Semites, later to be collectively known as

Akkadians lived alongside them. Akkadian ruled city states first

appear circa 2800 BC. In the 24th century BC the Akkadians gained

domination over the Sumerians under

Sargon the Great who founded the worlds first empire. By the 21st

century BC the

Akkadian Empire had collapsed, and the Akkadians split into

essentially two nations;

Assyria

and some time later,

Babylonia, although Babylonia was ruled by non native dynasties for

most of its history. According to the

Assyrian King List the earliest Assyrian king was a 23rd century BC

ruler named

Tudiya. Assyria became a strong nation in the 21st and 20th century

BC, founding colonies in

Asia Minor. In the 19th century BC a new wave of Semites, the

Amorites

entered Mesopotamia from the west, usurping the thrones of the Akkadian

states of

Assyria,

Isin and

Larsa, and founded

Babylon

as an independent City State The Amorite rulers turned Assyria

into a short lived imperial power from the late 19th century BC until

the mid 18th century BC, However, after its fall to Babylon they were

driven from Assyria by a king named

Adasi in

the late 18th Century BC, but eventually blended into the population of

Babylonia in the south. By approximately 1800 BC, the

Sumerian

race appears to have been wholly absorbed by the

Semitic

Akkadian population. According to the story told in the

Book of Genesis, it is around this time that the tribal leader

Abraham

travelled out of Mesopotamia and became the father of his people, the

Hebrews.

Assyria and later Babylon, became major powers. There were further

influxes of peoples such as

Hurrians,

Kassites

and

Mitanni, the Kassites ruled Babylon for over 500 years, and the

Mitanni dominated Assyria for a brief period. The Kassites, like the

Amorites before them, seem to have disappeared into the general

population in Babylonia, while the Mitanni and Hurrians were overthrown

and driven out of Assyria. Assyria then once again became a major

imperial power from 1365 BC until 1076 BC, rivalling Egypt.

In the 12th century BC a new influx of Semites from the west took

place, with the arrival of the

Arameans. The Arameans originally set up small kingdoms within

Mesopotamia, but were eventually brought under control and incorporated

into Assyria and Babylonia where they were culturally and politically

Akkadianized, and they ethnically intermixed and blended in with the

native Akkadian population.

It was not until the

Neo-Assyrian Empire (911-608 BC) and the influx and interbreeding

with

Aramean tribes that the Assyrians and Babylonians began to speak

Aramaic, the language of the

Aramaean tribes who had been assimilated into the Assyrian empire

and Mesopotamia in the 9th century BC.[31]

Mass relocations were enforced by Assyrian kings of the Neo-Assyrian

period.[32]

During the period of the Neo-Assyrian Empire many

Israelite

Jews were deported to Assyria and a fair proportion of these were

absorbed into the general population.

The Neo-Assyrian Empire (911 BC - 608 BC) saw a massive expansion of

Assyrian power, Assyria became the center of the greatest empire the

world had yet seen, with

Babylon,

Chaldea,

Persia,

Elam,

Media,

Gutium,

Israel,

Judah,

Aramea (modern

Syria),

Phonecia/Canaan,

Palestine,

Mannea, much of

Asia Minor (modern

Turkey),

the

Neo-Hittite states,

Corduene,

Egypt,

Cyprus, parts of the

Caucasus,

Dilmun,

Samaria,

Edom,

Nabatea and

Arabia brought under Assyrian control, the empire of

Urartu

defeated and conquered in the

Caucasus, the

Nubians,

Ethiopians and

Kushites defeated and driven from Egypt and the

Phrygians paying tribute to Assyria.

After the

fall of Nineveh

Following the distruction of the

Neo-Assyrian Empire by 608 BC, the population of the Assyria came

under the control of their Babylonian relatives until 539 BC. Ironically

Nabonidus, the last king of Babylonia was himself from Assyria. From

that time, Assyria as a political and named entity was under

Persian

Achaemenid,

Macedonian,

Seleucid,

Parthian

Arascid,

Roman and

Sassanid rule for seven centuries undergoing Christianization during

this time. Assyria flourished during the Achaemenid period (from 539-323

BC), becoming a major source of manpower for the Achaemenid armies and a

breadbasket for the empire, belieing the Biblical assertion that Assyria

was both depopulated and devastated.[33][34]

Assyrians are also attested as having important administrative posts

within the empire.

The

Seleucid empire succeeded that of the Achaemenids in 323 BC, from

this point

Greek became the official language of the empire at the expense of

Mesopotamian Aramaic. The general populace of Assyria were not

Hellenised however, as is attested by the survival of native language

and religion. The province flourished much as it had under the

Achaemenids for the next century, however by the late 3rd century BC

Assyria became a battleground between the Seleucid Greeks and the

Parthians but remained largely in Greek hands until the reign of

Mithridates I when it fell to the Parthians. During the

Seleucid period the term Assyria was altered to read Syria,

a Mediterranean form of the original name that had been in use since the

8th or 9th century BC among some western Assyrian colonies. The Seleucid

Greeks also named

Aramea to the west Syria (read Assyria) as it had been

an Assyrian colony for centuries. When they lost control of Assyria

proper (which is northern Mesopotamia, north east Syria and part of

south east Anatolia), they retained the name but applied it only to

Aramea (i.e.

The Levant). This created a situation where both Assyrians and

Arameans to the west were referred to as Syrians by the

Greco-Roman civilisations, causing the later Syrian Vs Assyrian

naming controversy. It was renamed

Assuristan during the Parthian era. The Parthians appeared to have

exercised only loose control at times, leading to the virtual

resurrection of Assyria with the native kingdom of

Adiabene 15 BC to 117AD.[35]

Its rulers were converts from

Mesopotamian religion to

Judaism

and later

Christianity, and it retained Mesopotamian Aramaic as its spoken

tongue.[35]

Adiabene, like the rest of northern Mesopotamia was conquered by

Trajan

in 117 AD, and the region was named

Assyria

by the

Romans. Christianity, as well as

Gnostic sects such as the

Sabians

and

Manicheanism took hold between the 1st and 3rd Centuries AD. The

Parthians regained control of the region a few years later, and retained

the name Assyria (Assuristan). Other small kingdoms had also sprung up

in the region, namely

Osrhoene and

Hatra,

which were

Aramaic/Syriac

speaking and at least partly Assyrian. Assyrian identity appears to have

remained strong, with the 2nd century writer and theologian

Tatian

stating clearly that he is an Assyrian, as does the satirist

Lucian

in the same period.

Assur

itself also appears to have been independent or largely autonomous, with

temples being dedicated to the national god of the Assyrians (Ashur)

into the second half of the 3rd Century AD, before it was once again

destroyed by the invading

Sassanids in 256 AD. The Sassanids recognised the land as Assyria,

retaining the name

Assuristan. Assyrians still seem to have retained a distinct

identity and a degree of local autonomy in the Sassanid period, during

the 4th century the region around

Nineveh

was governed by a certain local Assyrian king, who was pointedly named

Sennacherib, who established the

Mar Behnam monastery in memory of his son.[36]

In 341 AD, the

Zoroastrian

Shapur II ordered the massacre of all Christians in the Persian

Empire, most of whom were Assyrians. During the persecution, about 1,150

Christians were martyred under Shapur II.[37]

Assyria remained recognised as such by its inhabitants, Sassanid rulers

and neighbouring peoples until after the

Arab

Islamic conquest of the second half of the 7th century AD.

These Assyrians became

Christian in the first to third centuries.[38]

They were divided by the

Nestorian Schism in the fifth century, and from the eighth century,

they became both an

ethnic minority and a

religious minority following the

Arab

Islamic conquest of Mesopotamia.

Arab conquest

After the

Arab

Islamic invasion and conquest of the 7th century AD, Assyria as a

province was dissolved, but they continued to be referred to as

Ashuriyun by the Arabs. Assyrians initially experienced some periods

of religious and cultural freedom interspersed with periods of severe

religious and ethnic persecution. As heirs to ancient Mesopotamian

civilisation, they also contributed hugely to the Arab Islamic

Civilization during the

Ummayads and the

Abbasids by translating works of

Greek philosophers to

Syriac and afterwards to

Arabic. They also excelled in

philosophy,

science

and

theology ( such as

Tatian,

Bar Daisan,

Babai the Great,

Nestorius,

Toma bar Yacoub etc.) and the personal

physicians of the Abbasid Caliphs were often Assyrian

Christians such as the long serving

Bukhtishu dynasty.[39]

However, non-Islamic proselyting was punishable by death under

Sharia

law, which led the Assyrians into preaching in

Transoxania,

Central Asia,

India,

Mongolia and

China

where they established numerous churches. The

Church of the East was considered to be one of the major Christian

powerhouses in the world, alongside Latin Christianity in Europe and the

Byzantine Empire.[40]

From the 7th century AD onwards Mesopotamia saw a steady influx of

Arabs,

Kurds and other

Iranic people,[41]

and later

Turkic peoples, and those retaining native Mesopotamian culture,

identity, language, religion and customs were steadily marginalised and

gradually became a minority in their own homeland.[42]

This process of marginalisation was largely completed by the massacres

of indigenous Assyrian Christians and other non-Muslims in Mesopotamia

and its surrounds by

Tamerlane the

Mongol in the 14th century AD.[43]

However, many Assyrian Christians survived the various massacres and

pogroms, and resisted the process of

Arabization and

Islamification, retaining a distinct Mesopotamian identity,

Mesopotamian Aramaic language and written script. The modern

Assyrians or

Chaldo-Assyrians of today are descendants of the indigenous

inhabitants of Mesopotamia, and in particular Assyria, who refused to be

converted to Islam or be Arabized.

Culturally, ethnically and linguistically distinct from, although

both quite influencing on, and quite influenced by, their neighbours in

the Middle East�the

Arabs,

Persians,

Kurds,

Turks,

Jews and

Armenians � the Assyrians have endured much hardship throughout

their recent history as a result of

religious and

ethnic

persecution.[44][45]

Mongol and

Turkic rule

The region came under the control of the

Mongol Empire after the

fall of Baghdad in 1258. The Mongol khans were sympathetic with

Christians and didn't harm them. The most prominent among them was

probably

Isa Kelemechi, a diplomat, astrologer, and head of the Christian

affairs in the

Yuan Dynasty in China. He spent some time in Persia under the

Ilkhans. The 14th century AD massacres of

Timur in

particular, devastated the Assyrian people. Timur�s massacres and

pillages of all that was Christian drastically reduced their existence.

At the end of the reign of Timur, the Assyrian population had almost

been eradicated in many places. Toward the end of the thirteenth

century,

Bar Hebraeus (or Bar-Abraya), the noted Assyrian scholar and

hierarch, found �much quietness� in his diocese in Mesopotamia. Syria�s

diocese, he wrote, was �wasted.�

The region was later controlled by Turkic tribes such as the

Aq

Qoyunlu and

Qara Qoyunlu.

Seljuq and Arab emirate sought to extend their rule over the region

as well.

Ottoman rule

The Ottomans secured their control over Mesopotamia and Syria in the

16th century. Non-Muslims were organised into

millets. Syriac Christians, however, were often considered one

millet alongside

Armenians until the 19th century, when Nestorian, Syriac Orthodox

and Chaldeans gained that right as well.[46]

Hakkari massacre

In 1842 Assyrians living in the mountains of

Hakkari in south east

Anatolia faced a massive unprovoked attack from Ottoman forces and

Kurdish irregulars, which resulted in the death of tens of thousands of

unarmed Christian Assyrians.[47]

Hamidian massacres

A major massacre of Assyrians (and

Armenians) in the

Ottoman Empire occurred between 1894 and 1897 AD by

Turkish troops and their

Kurdish henchmen during the rule of

Sultan

Abdul Hamid II. The motives for these massacres were an attempt to

reassert

Pan-Islamism in the Ottoman Empire, resentment at the comparative

wealth of the ancient indigenous Christian communities, and a fear that

they would attempt to secede from the tottering Ottoman Empire.

Assyrians were massacred in

Diyarbakir,

Hasankeyef,

Sivas and

other parts of Anatolia, by Sultan Abdul Hamid II. These attacks caused

the death of over thousands of Assyrians and the forced "Ottomanisation"

of the inhabitants of 245 villages. The Turkish troops looted the

remains of the Assyrian settlements and these were later stolen and

occupied by Kurds. Unarmed Assyrian women and children were raped,

tortured and murdered.[47]

Assyrian genocide

The most significant recent persecution against the Assyrian

population was the

Assyrian genocide, which occurred at the onset of the First World

War (1914-1918 AD). Between 500,000 and 750,000 Assyrians were estimated

to have been slaughtered by the armies of the

Ottoman Empire and their

Kurdish allies, totalling up to two-thirds of the entire population.

This led to a large-scale resettlement of Turkish based Assyrian people

in countries such as Syria, Iran and Iraq (where they suffered further

violent assaults at the hands of the

Arabs), as well as other neighbouring countries in and around the

Middle East such as

Armenia,

Republic of Georgia and

Russia.[48][49][50][51]

Modern history

Simele massacre

The

Simele Massacre was the first of many massacres committed by the

Iraqi Government during the systematic targeting of Assyrians of

Northern Iraq in August 1933. The term is used to describe not only the

massacre of Simele, but also the killing spree that continued among 63

Assyrian villages in the

Dohuk and

Mosul districts that led to the deaths of an estimated 3,000 or more

civilian Assyrians.

Arab

Ba'athist persecution

The

Ba'ath Party seized power in

Iraq and

Syria in 1963, which introduced laws that aimed at suppressing the

Assyrian national identity, the Arab Nationalist policies of the

Ba'athists included renewed attempts to "Arabize" the Assyrians. The

giving of traditional Assyrian/Akkadian names and Aramaic/Syriac

versions of Biblical names was banned, Assyrian schools, political

parties, churches and literature were repressed and Assyrians were

heavily pressured into identifying as Arab Christians. The

Ba'athist regime refused to recognise Assyrians as an ethnic group.[52]

The

al-Anfal Campaign of 1986-1989 in Iraq was predominantly aimed at

Kurds, however it saw many Assyrian towns and villages razed to the

ground, a number of Assyrians were murdered, others were deported to

large cities, their land and homes then being appropriated by Arabs and

Kurds.[53]

Kurdish

persecution

After the established of the

Kurdish Regional Government after 1991, the Kurdish Parliament

passed a few laws permitting Kurdish settlers to seize lands owned by

Assyrians. Assyrians, together with other ethnic minorities in northern

Iraq, have since suffered a great degree of discrimination and pressure

from Kurdish Nationalists, this includes the officially sanctioned theft

of Assyrian land, political intimidation against Assyrian political

parties, ethnic and religious discrimination and a number of kidnappings

and murders.

[52][54][55]

Iraq

War & Islamist attacks

Since the

Iraq

War started in 2003, social unrest and anarchy have resulted in

unprovoked persecution of Assyrians in Iraq, mostly by

Islamic extremists,(both

Shia and

Sunni), and to some degree by

Kurdish

Nationalists. In places such as

Dora, a neighborhood in southwestern

Baghdad,

the majority of its Assyrian population has either fled abroad, to

northern Iraq or been murdered.[56]

Islamic resentment over the United States occupation of Iraq, and

incidents such as the

Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons and the

Pope Benedict XVI Islam controversy, have resulted in their

attacking the Assyrian Christian communities. Since the start of the

Iraq war, at least 46 churches and monasteries have been bombed.[57]

However, the new Iraqi government now officially recognises Assyrians

ethnic and cultural identity, listing them as

Chaldo-Assyrians (Ironically something the "Western Media" often

refuses to do). The idea of an Assyrian homeland has not been rejected,

and the ban on the giving of Assyrian names, teaching the Assyrian

language and on Assyrian schools has been lifted. Assyrians have formed

armed militias in an around Assyrian towns, villages and districts.

Many of the Assyrians who have suffered violent attacks in

predominantly Arab Muslim cities such as

Baghdad,

Nasiriyah and

Basra

have moved north to their traditional homeland and are now congregating

there, boosting numbers (A number of the ethnically and linguistically

related

Mandeans are doing the same). There has also been some small scale

resettlement over the border in south east Turkey.

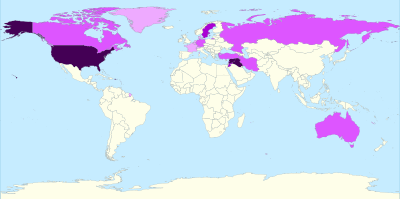

Demographics

Assyrian world popualtion.

more than 500,000

100,000 - 500,000

50,000 - 100,000

10,000 - 50,000

Homeland

The Assyrians are considered to be one of the indigenous people in

the Middle East. Their homeland was thought to be located in the area

around the

Tigris and

Euphrates. Assyrians are traditionally from

Iraq, south

eastern

Turkey, north western

Iran and

north eastern

Syria. There is a significant Assyrian population in Syria, where an

estimated 877,000 Assyrians live.[58]

Though it must be pointed out that

Syriac Christians from western, central and southern Syria are not

generally regarded as Assyrians but rather as

Arameans. The true Assyrians of Syria reside mainly in northeastern

and eastern Syria, particularly in the

Al-Hasakah

region. In

Tur

Abdin, known as a homeland for Assyrians, there are only 3,000 left,[59]

and an estimated 25,000 in all of Turkey.[60]

After the 1915

Assyrian genocide many Assyrians/Syriacs also fled into Lebanon,

Jordan, Iran, Iraq and into the

Western world.

The Assyrian/Syriac people can be divided along geographic,

linguistic, and denominational lines, the three main groups being:

Diaspora

Since the

Assyrian Genocide, many Assyrians have fled their homelands for a

more safe and comfortable life in the West. Since the beginning of the

20th century, the Assyrian population in the Middle East has decreased

dramatically. As of today there are more Assyrians in Europe, North

America, and Australia than in their former homeland.

A total of 550,000 Assyrians live in Europe.[61]

Large Assyrian/Chaldean/Syriac diaspora communities can be found in

Germany, Sweden, the USA, and Australia. The largest Assyrian/Chaldean/Syriac

diaspora communities are those of

S�dert�lje,

Chicago,

and

Detroit.

Identity

Chaldean flag (since 1997) [63]

Assyrians are divided among several churches (see below). They speak,

and many can read and write, dialects of

Neo-Aramaic.[65]

In certain areas of the

Assyrian homeland, identity within a community depends on a person's

village of origin (see

List of Assyrian villages) or Christian denomination rather than

their ethnic commonality, for instance

Chaldean Catholic.[66]

Today, Assyrians and other minority ethnic groups in the Middle East,

feel pressure to identify as "Arabs",[67][68]

"Turks" and "Kurds".[69]

Assyrians in Syria who live outside of the traditionally and

historically Assyrian northeastern region of the country are

disappearing as an ethnic group, due to assimilation.[citation

needed]

Neo-Aramaic exhibits remarkably conservative features compared with

Imperial Aramaic,[70]

and the earliest European visitors to northern Mesopotamia in modern

times encountered a people called "Assyrians" and men with ancient

Assyrian names such as Sargon and Sennacherib.[71][72][73]

The Assyrians manifested a remarkable degree of linguistic, religious,

and cultural continuity from the fall of the

Neo-Assyrian Empire through to the time of the ancient Greeks,

Persians, and Parthians through periods of medieval Byzantine, Arab,

Persian, and Ottoman rule.[74]

Assyrian nationalism emphatically connects Modern Assyrians to the

population of the

Neo-Assyrian Empire. A historical basis of this sentiment has been

disputed by a few early historians,[75]

but receives support from modern

Assyriologists like

H.W.F. Saggs,

Robert D. Biggs,

Giorgi Tsereteli and

Simo Parpola,[76][77][78]

and

Iranologists like

Richard Nelson Frye.[79][80]

Nineteenth century orientalists such as

Austen Henry Layard and

Hormuzd Rassam also support this view. This controversy does not

appear to exist in parts of the region however, as Armenian, Georgian,

Russian, Persian and some Arab records have always referred to Assyrians

as Assyrians.

Self-designation

The various communities of indigenous Pre Arab

Neo-Aramaic-speaking people of

Iraq,

Syria,

Iran,

Turkey

and

Lebanon and the surrounding areas advocate different terms for

ethnic self-designation. It may be the case that the "Assyrian/Chaldo-Assyrian/Eastern

Syriac" group and the "Aramean"/"Western Syriac" and "Phoenician" groups

are merely closely related and not in fact exactly the same

people.

- "Assyrians", after the ancient

Assyria,

advocated by followers of the

Assyrian Church of the East, the

Ancient Church of the East, most followers of the

Chaldean Catholic Church and Assyrian

Protestants. ("Eastern Assyrians"),[81]

and some communities of the

Syriac Orthodox and

Syriac Catholic ("Western Assyrians"). Those identifying with

Assyria,

and with

Mesopotamia in general, tend to be from

Iraq,

north eastern

Syria,

south eastern

Turkey,

Iran,

Armenia,

Georgia, southern

Russia

and

Azerbaijan. It is likely that those from this region are indeed of

Assyrian/Mesopotamian heritage as they are clearly of Pre Arab

and pre Islamic stock and furthermore, there is no historical

evidence, let alone proof to suggest the indigenous Mesopotamians were

wiped out, and of course Assyria did exist as a specifically named

region until the second half of the 7th century AD. Most speak various

Mesopotamian dialects of

neo Aramaic.

- "Chaldo-Assyrians",

is a term used by the Iraqi government to designate the indigenous

Aramaic speaking Christians of Iraq. It intrinsically acknowledges

that both the term Assyrian and Chaldean refer to the same ethnic

group. Some Assyrians also use this term in order to defuse arguments

over naming along denominational lines.

- "Chaldeans",

after ancient

Chaldea,

advocated by a minority of followers of the

Chaldean Catholic Church who are mainly based in the

United States. This is mainly a denominational rather than

ethnic term, though a few Chaldean Catholics espouse a distinct

Chaldean ethnic identity. However it is likely that these are exactly

the same people as the Assyrians, both having the same culture and

originating from the same lands.

- "Syriacs",

advocated by some followers of the

Syriac Orthodox Church,

Syriac Catholic Church and to a much lesser degree

Maronite Church. Those self identifying as Syriacs tend to be from

western, northwestern,southern and central

Syria

as well as south central

Turkey.

The term Syriac is the subject of some controversy, as it is

generally accepted by most scholars that it is a

Luwian and

Greek

corruption of Assyrian. The discovery of the

�inek�y inscription seems to settle conclusively in favour of

Assyria being the origin of the terms Syria and Syriac. For this

reason, some Assyrians also accept the term Syriac as well as Assyrian

as it is taken to mean the same thing. It is likely that Syriacs from

these regions are in fact Arameans rather than Assyrians, as

geographically they are not from Mesopotamia or the immediate areas

surrounding it. Only a minority of those identifying as Syriacs now

speak Aramaic, and most are now Arabic speaking.

Other groups of "Syriac Christians" are geographically,

linguistically and ethnically separate from the "Assyrian/Chaldo-Assyrian/Syriac"

people. There include;

- "Arameans"

advocated by a number of indigenous Christians in western,

northwestern,southern and central

Syria

as well as south central

Turkey.

They reject the term Syriac because of its probable Assyrian

origin, and because they are not in fact geographically from Assyria

or Mesopotamia in general, but rather are pre Arab inhabitants

of lands that encompass the traditional Aramean homeland, which is in

effect most of modern Syria. Few of those identifying as Aramean now

speak Aramaic, and most are now Arabic speaking.

- "Phoenicians"

Many Maronites identify with a

Phoenician origin however and do not see themselves as Syriac or

Aramean. These tend to be from

Lebanon

and the Mediterranean coast of

Syria,

an area roughly corresponding to ancient Phoenicia. They are of pre

Arab and pre Islamic origin, and thus identify with the

ancient pre Arab and pre Islamic population of that region.

In addition

Western Media often makes no mention whatsoever of any ethnic

identity of the Christian people of the region, and simply call them

Christians or Iraqi Christians, Iranian Christians,

Syrian Christians, Turkish Christians etc. This label is

rejected by all Assyrian/Syriac Christians as well as Aramean,

Phoenician and Coptic Christians, as it wrongly implies no difference

other than theological with the Muslim Arabs, Kurds, Turks, Iranians and

Azeris of the region.

Assyrian vs Syrian naming controversy

As early as the 8th century BC

Luwian and

Cilician subject rulers referred to their Assyrian overlords as

Syrian, a western

Indo-European bastardisation of the true term Assyrian. This

corruption of the name took hold in the Hellenic lands to the west of

the old Assyrian Empire, thus during

Greek

Seleucid rule from 323 BC the name Assyria was altered to

Syria, and this term was also applied to

Aramea to the west which had been an Assyrian colony. When the

Seleucids lost control of Assyria to the

Parthians they retained the corrupted term (Syria), applying it to

ancient Aramea, while the Parthians called Assyria

Assuristan, a Parthian form of the original name. It is from this

period that the Syrian vs Assyrian controversy arises. Today it is

accepted by the majority of scholars that the Medieval, Renaissance and

Victorian term Syriac when used to describe the indigenous

Christians of Mesopotamia and its immediate surrounds in effect means

Assyrian.[82]

The modern terminological problem goes back to colonial times, but it

became more acute in 1946, when with the independence of Syria, the

adjective Syrian referred to an independent state. The

controversy isn't restricted to

exonyms like English "Assyrian" vs. "Aramaean", but also applies to

self-designation in

Neo-Aramaic, the minority "Aramaean" faction endorses both

Sūryāyē

ܣܘܪܝܝܐ and Ārāmayē

ܐܪܡܝܐ, while the majority "Assyrian" faction

insists on Āṯūrāyē

ܐܬܘܪܝܐ but also accepts Sūryāyē

ܣܘܪܝܝܐ.

Alqosh, located in the midst of Assyrian contemporary

civilization.

The question of ethnic identity and self-designation is sometimes

connected to the scholarly debate on the

etymology of "Syria". The question has a long history of academic

controversy, but majority mainstream opinion currently strongly favours

that Syria is indeed ultimately derived from the Assyrian term

𒀸𒋗𒁺 𐎹 A��ūrāyu.[80][83][84]

Meanwhile, some scholars has disclaimed the theory of Syrian being

derived from Assyrian as "simply naive", and detracted its importance to

the naming conflict.[85]

Rudolf Macuch points out that the Eastern Neo-Aramaic press initially

used the term "Syrian" (sury�ta) and only much later, with the

rise of nationalism, switched to "Assyrian" (ator�ta).[86]

According to Tsereteli, however, a

Georgian equivalent of "Assyrians" appears in ancient Georgian,

Armenian and Russian documents.[87]

This correlates with the theory of the nations to the East of

Mesopotamia knew the group as Assyrians, while to the West, beginning

with Greek influence, the group was known as Syrians. Syria being a

Greek corruption of Assyria.

The debate appears to have been settled by the discovery of the

�inek�y inscription in favour of Syria being derived from Assyria.

The �inek�y inscription is a

Hieroglyphic Luwian-Phoenician

bilingual, uncovered from �inek�y,

Adana Province, Turkey (ancient

Cilicia),

dating to the

8th century BC. Originally published by Tekoglu and Lemaire (2000),[88]

it was more recently the subject of a 2006 paper published in the

Journal of Near Eastern Studies, in which the author, Robert

Rollinger, lends support to the age-old debate of the name "Syria" being

derived from "Assyria" (see

Etymology of Syria).

The object on which the inscription is found is a monument belonging

to Urikki,

vassal king of

Hiyawa

(i.e.

Cilicia), dating to the

eighth century BC. In this monumental inscription, Urikki made

reference to the relationship between his kingdom and his

Assyrian overlords. The Luwian inscription reads "Sura/i" whereas

the Phoenician translation reads ��R or "Ashur" which, according

to Rollinger (2006), "settles the problem once and for all".[89]

Culture

Assyrian child dressed in traditional clothes.

Assyrian culture is largely influenced by religion.[90]

The language is tied to the church as well for it uses the Syriac

language in liturgy.[clarification

needed] Festivals occur during religious holidays

such as Easter and Christmas. There are also secular holidays such as

Kha b-Nisan (vernal equinox).[91]

People often greet and bid relatives farewell with a kiss on each

cheek and by saying "Peace be upon you." Others are greeted with a

handshake with the right hand only; according to Middle Eastern customs,

the left hand is associated with evil. Similarly, shoes may not be left

facing up, one may not have their feet facing anyone directly, whistling

at night is thought to waken evil spirits, etc.[92]

There are many Assyrian customs that are common in other Middle

Eastern cultures. A parent will often place an eye pendant on their baby

to prevent "an evil eye being cast upon it".[93]

Spitting on anyone or their belongings is seen as a grave insult.

Language

The

Neo-Aramaic languages are ultimately descended from

Old Aramaic, the lingua franca in the later phase of the

Neo-Assyrian Empire, displacing the

East Semitic

Assyrian dialect of Akkadian. Aramaic was the language of commerce,

trade and communication and became the vernacular language of Assyria in

classical antiquity.[94][95][96]

By the 1st century AD, Akkadian was extinct, although some loaned

vocabulary still survives in Assyrian Neo-Aramaic to this day.[97][98]

Most Assyrians speak an

Eastern Aramaic language whose

dialects

include

Chaldean and

Turoyo as well as

Assyrian.[99]

All are classified as

Neo-Aramaic languages and are written using

Syriac script, a derivative of the ancient

Aramaic script. Assyrians also may speak one or more languages of

their country of residence.

To the native speaker, "Syriac" is usually called Soureth or

Suret. A wide variety of dialects exist, including

Assyrian Neo-Aramaic,

Chaldean Neo-Aramaic, and

Turoyo. Being

stateless, Assyrians also learn the language or languages of their

adopted country, usually

Arabic,

Armenian,

Persian or

Turkish. In northern Iraq and western Iran,

Turkish and

Kurdish is widely spoken.

Recent archaeological evidence includes a statue from

Syria

with

Assyrian and

Aramaic inscriptions.[100]

It is the oldest known Aramaic text.

Religion

Assyrians were originally

Pagans,

who where followers of

Ashurism, an

Assyro-Babylonian religion, which is the Ancient

Mesopotamian religion, and some adopted

Judaism,

Gnosticism and

Manicheanism; however most now belong to various

Christian denominations such as the

Church of the East, with an estimated 300,000�400,000 members,[101]

the Chaldean Catholic Church, with about 900,000 members,[102]

and the

Syriac Orthodox Church (ʿIdto Suryoyto

Triṣaṯ �uḇḥo), which has between 1,000,000 and 4,000,000

members around the world (only some of whom are Assyrians),[103]

and various

Protestant churches. While Assyrians are predominantly

Christians, a number are generally

irreligious.

As of 2011

Mar Dinkha IV, resident in Chicago Illinois, was

Patriarch of the

Assyrian Church of the East,

Mar Addai II, with headquarters in

Baghdad,

was Patriarch of the

Ancient Church of the East, and

Ignatius Zakka I Iwas was Patriarch of the

Syriac Orthodox Church, with headquarters in

Damascus.

Mar Emmanuel III Delly, the Patriarch of the

Chaldean Catholic Church, was the first Patriarch to be elevated to

Cardinal, joining the

college of cardinals in November 2007.

Many members of the following churches consider themselves Assyrian.

Ethnic identities are often deeply intertwined with religion, a legacy

of the Ottoman

Millet system. The group is traditionally characterized as adhering

to various churches of

Syriac Christianity and speaking

neo-Aramaic languages. It is subdivided into:

- adherents of the

East Syrian Rite, always called Assyrians but in the past

sometimes erroneously called Nestorians

- adherents of the

West Syrian Rite, called Syriacs, and formerly also

Jacobites.

A small minority of Assyrians of the above denominations accepted the

Protestant Reformation in the 20th century, possibly due to British

influences, and is now organized in the

Assyrian Evangelical Church, the

Assyrian Pentecostal Church and other Protestant Assyrian groups.

These are always called Assyrians

Baptism and First Communion are celebrated extensively, similar to a

Bris or

Bar Mitzvah in Jewish communities. After a death, a gathering is

held three days after burial to celebrate the ascension to heaven of the

dead person, as of

Jesus;

after seven days another gathering commemorates their passing. A close

family member wears only black clothes for forty days and nights, or

sometimes a year, as a sign of mourning.

Music

Assyrian/Syriacs playing Zoorna and Dahola

The

abooba ܐܒܘܒܐ (basic flute) and

ṭavla

ܛܒ݂ܠܐ (large two-sided drum) became the most common musical instruments

for tribal music. Some well known Assyrian/Syriac singers in modern

times are

Ashur Bet Sargis,

Sargon Gabriel,

Michael Dayan,

Habib Mousa,

Josef �zer,

Janan Sawa,

Klodia Hanna,

Juliana Jendo, and

Linda George.

The first International

Aramaic Music Festival was held in Lebanon from 1 August until 4

August 2008 for Assyrian people internationally. Assyrians are also

involved in western contemporary music, such as Rock/Metal (Melechesh),

Rap (Timz)

and Techno/Dance (Aril

Brikha).

Dance

Assyrians have numerous traditional

dances

which are performed mostly for special occasions such as weddings.

Assyrian dance is a blend of both ancient indigenous and general near

eastern elements.

Festivals

Assyrian/Syriac festivals tend to be closely associated with their

Christian faith, of which

Easter

is the most prominent of the celebrations. Assyrian/Syriac members of

the Assyrian Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic Church and Syriac

Catholic Church follow the

Gregorian calendar and as a result celebrate Easter on a Sunday

between March 22 and April 25 inclusively.[104]

While Assyrian/Syriac members of the Syriac Orthodox Church and Ancient

Church of the East celebrate Easter on a Sunday between April 4 and May

8 inclusively on the Gregorian calendar (March 22 and April 25 on the

Julian calendar). During

Lent

Assyrian/Syriacs are encouraged to fast for 50 days from meat and any

other foods which are animal based.

Assyrians celebrate a number of festivals unique to their culture and

traditions as well as religious ones:

-

Kha b-Nisan, the Assyrian new year, traditionally on

April 1,

though usually celebrated on Jaunuary 1. Assyrians usually wear

traditional costumes and hold social events including parades and

parties, dancing, and listening to poets telling the story of

creation.

- Som Baoutha, the Nineveh fest. It is a three-day period of fasting

and prayer.

- Somikka, the Assyrian version of

Halloween, traditionally meant to scare children into fasting

during Lent.

Assyrians also practice unique marriage ceremonies. The rituals

performed during weddings are derived from many different elements from

the past 3,000 years. An Assyrian wedding traditionally lasted a week.

Today, weddings in the Assyrian homeland usually last 2�3 days; in the

Assyrian diaspora they last 1�2 days.

Traditional

clothing

Assyrian clothing varies from village to village. Clothing is usually

blue, red, green, yellow, and purple; these colors are also used as

embroidery on a white piece of clothing. Decoration is lavish in

Assyrian costumes, and sometimes involves jewellery. The conical hats of

traditional Assyrian dress have changed little over millennia from those

worn in ancient Mesopotamia, and until the 19th and early 20th centuries

the ancient Mesopotamian tradition of braiding or platting of hair,

beards and moustaches was still commonplace.

Cuisine

Assyrian cuisine is similar to other Middle Eastern cuisines. It is

rich in

grain, meat,

potato,

cheese,

bread and

tomato.

Typically rice

is served with every meal, with a stew poured over it.

Tea is a

popular drink, and there are several dishes of desserts, snacks, and

beverages.

Alcoholic

drinks such as

wine and

wheat beer are organically produced and drunk.

Names

Distinctively

Akkadian language names are attested into the

Sassanid period (224 AD to 651 AD), before they were generally but

not wholly replaced by Christian names.

Biblical names in English/Arabic/Syriac

variants are a Syriac tradition. Names such as

Daniyyel/Daniel,

Dawid,

Gabriel,

Michael/Mikhail,

Gorges/Gewargis (George),

Yaqo/Yako (Jacob),

Yausep/Yosef (Joseph),

Toma (Thomas),

Peṭros (Peter),

Yoḥannan/Ewan/Yonan/Younan,

Yaunan

(John/Jonathan),

Iliya,

Eshu/Esho

(Jesus),

Ishai (Jesse) and

Meriam (Mary) are of clear religious origin, although many are of

Aramaic origin.

Children are often given Biblical names, and, by Assyrian/Syriac

patriots and traditionalists, Assyrian, Aramean and Akkadian names are

given such as Ashur,

Aram, Sinharib/Senacherib, Sargon,

Shammiram, Ninus, Nimrod, Abgar, Aram,

Afrem, and Aryu, etc... Akkadian last names are still

common, such as; Ashur, Shamash, Akkad, Hadad, Dayan, Obelit etc.

French and

English names are also given:

Jean,

Pierre,

James. Names of Turkish and Arab origin are also prominent, for

instance, Assyrians in south-eastern Turkey (Tur

Abdin,

Midyat) have predominantly Turkish surnames as a result of the

Turkish law that forbids Assyrians to give their children Assyrian

names.

Tribal and Clan names are often still used, normally with the

Akkadian prefix Bit or neo-Aramaic prefix Bet (meaning

house of, or people of), such as Bit Kasri, Bit Tiyari,

Bit Eshtazin, Bit Bazi, Bit Shamasha etc.

Physical

Appearance

Assyrians are of

Caucasoid appearance, more specifically of a Near

Eastern/Mediterranean type. In general, they tend to be olive skinned,

with black or dark brown hair and dark eyes.

Aquiline noses are common among many Assyrians. However, a number of

Assyrians also have fair hair, fairer or browner skin and lighter eyes.

Genetics

Late 20th century DNA analysis conducted by

Cavalli-Sforza,

Paolo Menozzi and

Alberto Piazza, "shows that Assyrians have a distinct genetic

profile that distinguishes their population from any other population."[105]

Genetic analysis of the Assyrians of Persia demonstrated that they were

"closed" with little "intermixture" with the Muslim Persian population

and that an individual Assyrian's genetic makeup is relatively close to

that of the Assyrian population as a whole.[106]

Cavalli-Sforza

et al. state in addition, "[T]he Assyrians are a fairly homogeneous

group of people, believed to originate from the land of old Assyria in

northern Iraq", and "they are Christians and are possibly

bona fide descendants of their namesakes."[107]

"The genetic data are compatible with historical data that religion

played a major role in maintaining the Assyrian population's separate

identity during the Christian era".[105]

A 2008 study on the genetics of "old ethnic groups in Mesopotamia,"

including 340 subjects from seven ethnic communities ("Assyrian, Jewish,

Zoroastrian, Armenian, Turkmen, and Arab peoples of Iran, Iraq, and

Kuwait") found that Assyrians were homogeneous with respect to all other

ethnic groups sampled in the study, regardless of religious affiliation.[108]

In a 2006 study of the Y chromosome DNA of six regional Armenian

populations, including, for comparison, Assyrians and Syrians,

researchers found that, "the Semitic populations (Assyrians and

Syrians) are very distinct from each other according to both

[comparative] axes. This difference supported also by other methods of

comparison points out the weak genetic affinity between the two

populations with different historical destinies."

[109] It must be pointed out that genetic studies purporting

to either prove or disprove any modern population's ancient ancestry are

the subject of a degree of controversy, and it is notoriously difficult

to conclusively prove either way with DNA studies.[citation

needed]

See also

References

-

^

also transliterated

Sūrōyē /

Sūryōyē /

Ōṯūrōyē; all of

ā,

ō and word-final

ē transliterate Aramaic

Ālaph

ܐ. Nicholas Awde, Nineb Limassu, Nicholas Al-Jeloo,

Modern Aramaic Dictionary & Phrasebook: (Assyrian/Syriac)

(2007),

ISBN 9780781810876, p. 4; see also

Names of Syriac Christians.

-

^

[1],

UNPO estimates

-

^

SIL Ethnologue estimate for the "ethnic population" associated

with Assyrian Neo-Aramaic.

[2]

-

^

[3],

CIA World Factbook

-

^

Christians in Iraq GlobalSecurity.org total estimated to be some

500,000 after the

Iraq war

-

^

Iraqi Christians' long history,

BBC

-

^

[4]

-

^

Assyrians Face Escalating Abuses in "New Iraq", Lisa S�derlindh,

Inter Press Service 1,139,000 including some 300,000 Assyrian

refugees from Iraq

- ^

a

b

c

atour.com name="Population" _moz_dirty="" Population, atour.com

-

^

[5],

SIL Ethnologue "Assyrian Neo-Aramaic 15,000 in Iran (1994).

Ethnic population: 80,000 (1994)" See also

Christianity in Iran.

-

^

[6],

SIL Ethnologue "Turoyo [tru] 3,000 in Turkey (1994 Hezy Mutzafi).

Ethnic population: 50,000 to 70,000 (1994). H�rtevin [hrt] 1,000

(1999 H. Mutzafi). Originally Siirt Province. They have left their

villages, most emigrating to the West, but some may still be in

Turkey." See also

Christianity in Turkey.

-

^

Brief History of Assyrians, AINA.org

-

^

Demographics of Sweden,

Swedish Language Council "Sweden has also one of the largest

exile communities of Assyrian and Syriac Christians (also known as

Chaldeans) with a population of around 100,000."

-

^

Brief History of Assyrians, AINA.org

-

^

American Community Survey,

U.S. Census Bureau

-

^

Thrown to the Lions,

Doug Bandow, The America Spectator

-

^

Jordan Should Legally Recognize Displaced Iraqis As Refugees,

AINA.org.

Assyrian and Chaldean Christians Flee Iraq to Neighboring Jordan,

ASSIST News Service

-

^

70,000 Syriac Christians according to

REMID (of which 55,000

Syriac Orthodox).

-

^

Ancestry (full classification list)

Australian Bureau of Statistics

-

^

[7][8]

More than two thirds of Iraqis in Australia (80,000) are Christians

-

^

http://www.radiovaticana.org/en1/articolo.asp?c=49496

- ^

a

b

c

d

e

f

g

Brief History of Assyrians, AINA.org

-

^

so identified in the

United States Census

-

^

an anglicization of the

Aramaic name, also as Suraye/Suryaye; e.g. in Al-Ali et

al., New Approaches to Migration? (Routledge 2002, p. 20)

used synonymously with "Syriac Christians".

-

^ *MacDonald,

Kevin (2004-07-29).

Socialization for Ingroup Identity among Assyrians in the United

States. Paper presented at a symposium on socialization for

ingroup identity at the meetings of the International Society for

Human Ethology,

Ghent, Belgium. "Based on interviews with community informants,

this paper explores socialization for ingroup identity and endogamy

among Assyrians in the United States. The Assyrians descent from the

population of ancient

Assyria (founded in the 23rd century BC), and have lived as a

linguistic,

political,

religious, and

ethnic minority in

Iraq,

Iran,

Syria

and

Turkey since the fall of the Assyrian Empire in 608 B.C.

Practices that maintain ethnic and cultural continuity in the

Near East, the

United States and elsewhere include language and residential

patterns, ethnically based

Christian

churches characterized by unique

holidays and

rites,

and culturally specific practices related to life-cycle events and

food preparation. The interviews probe parental attitudes and

practices related to ethnic

identity and encouragement of

endogamy. Results are being analyzed.".

-

^

Assyrians in Georgia,

Joshua Project

-

^

Dr. Eden Naby.

"Documenting The Crisis In The Assyrian Iranian Community".

-

^

"Assyrian Christians 'Most Vulnerable Population' in Iraq". The

Christian Post. Retrieved

2006-12-05.

-

^

"Iraq's Christian community, fights for its survival". Christian

World News.

-

^

"U.S. Gov't Watchdog Urges Protection for Iraq's Assyrian

Christians". The Christian Post.

Retrieved 2007-12-31.

-

^

Parpola, Simo (2004).

"National and Ethnic Identity in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and

Assyrian Identity in Post-Empire Times" (PDF).

Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies (JAAS) 18 (2):

pp. 8�9.

-

^

Hooker, Richard.

"Mesopotamia, the Assyrians, 1170�612, The Assyrian Period".

Washington State University.

-

^ Bertman, Stephen (2005).

Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. New York: Oxford UP.

p. 244.

ISBN 0816043469.

-

^

Arrian,

Anabasis, III.7.3.

- ^

a

b George Roux- Ancient Iraq

-

^

Wolff, Joseph.

Missionary Journal and Memoir. p. 279.

-

^

http://ocafs.oca.org/Caption.asp?FSID=101122

-

^

Parpola, Simo (2004).

"National and Ethnic Identity in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and

Assyrian Identity in Post-Empire Times" (PDF).

Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies (JAAS) 18 (2):

pp. 21. "From the third century AD on, the Assyrians embraced

Christianity in increasing numbers".

-

^

R�mi Brague,

Assyrians contributions to the Islamic civilization

-

^

Winkler, Dietmar (2009).

Hidden Treasures And Intercultural Encounters: Studies On East

Syriac Christianity In China And Central Asia. LIT Verlag

M�nster.

-

^

Aboona, Hirmis (2008).

Assyrians, Kurds, and Ottomans: intercommunal relations on the

periphery of the Ottoman Empire.

-

^

Khanbaghi, Aptin (2006).

The fire, the star and the cross: minority religions in medieval

and early modern Iran. I.B.Tauris.

-

^

Khanbaghi, Aptin (2006).

The fire, the star and the cross: minority religions in medieval

and early modern Iran. I.B.Tauris.

-

^

Parpola, National and Ethnic Identity in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and

Assyrian Identity in Post-Empire Times, pp. 21

-

^

"Assyrians". World Culture Encyclopedia.

-

^

The Blackwell companion to Eastern Christianity, Kenneth Parry

- ^

a

b

http://aua.net/assyrians/genocide/genocide_presentation.htm

-

^

The Plight of Religious Minorities: Can Religious Pluralism Survive?

- Page 51 by United States Congress

-

^

The Armenian Genocide: Wartime Radicalization Or Premeditated

Continuum - Page 272 edited by Richard Hovannisian

-

^

Not Even My Name: A True Story - Page 131 by Thea Halo

-

^

The Political Dictionary of Modern Middle East by Agnes G. Korbani

- ^

a

b

Iraq: Information on Treatment of Assyrian and Chaldean Christians,

UNHCR

-

^

The Anfal Offensives, indict.org.uk

-

^

Northern Iraq Parliament Resolves to Transfer Assyrian Lands to

Kurdish Squatters, AINA.org

-

^

Kurdish Land Grabs Leave Assyrians Dependent on Food Aid,

AINA.org

-

^

Exodus of Christians Hits Baghdad district,

The Boston Globe

-

^

"Church Bombings in Iraq Since 2004". Aina.org.

Retrieved 2008-11-16.

-

^

[9],

SIL Ethnologue

-

^ *SOC

News report , He was documenting life in the Tur Abdin, where

about 3,000 members of the Aramean minority still live.'

-

^

Statement on Assyrians/Syriacs in Turkey/Iraq

-

^

http://www.turkishdailynews.com.tr/article.php?enewsid=70134

-

^

"Assyria". Crwflags.com.

Retrieved 2008-11-16.

-

^

Chaldean Flag Day: May 17th

-

^

"Syriac-Aramaic People (Syria)". Crwflags.com.

Retrieved 2008-11-16.

-

^

Florian Coulmas, The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Writing Systems 23

(1996)

-

^

Note on the Modern Assyrians

-

^

Iraqi Assyrians: A Barometer of Pluralism

-

^

"Arab American Institute Still Deliberately Claiming Assyrians Are

Arabs". Aina.org. Retrieved

2008-11-16.

-

^

"In Court, Saddam Criticizes Kurdish Treatment of Assyrians".

Aina.org. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

-

^

J.G. Browne, "The Assyrians", Journal of the Royal Society of

Arts 85 (1937)

-

^

George Percy Badger, The Christians of Assyria Commonly

Called Nestorians (London: W.H. Bartlett, 1869)

-

^

J.F. Coakley, The Church of the East and the Church of England

(Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992), pp. 5, 89, 99, 149, 366�67, 382,

411

-

^

Michael D. Coogan, ed., The Oxford History of the Biblical World

(New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 279

-

^

"Parthia", in The Cambridge Ancient History: The Roman Republic,

2nd ed., vol. 3, pt. 2 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,

1991), 597�98; Patricia Crone and Michael Cook, Hagarism: The

Making of the Islamic World (Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 1980), 55�60; "Ashurbanipal and the Fall of Assyria", in

The Cambridge Ancient History: The Assyrian Empire, vol. 3

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1954), 130�31; A.T.

Olmstead, History of the Persian Empire (Chicago: University

of Chicago Press, 1948), 168; Albert Hourani, Minorities in the

Arab World (London: Oxford University Press, 1947), 99; Aubrey

Vine, The Nestorian Churches (London: Independent Press,

1937); Flavius Josephus, The Antiquities of the Jews, trans.

William Whiston (1737), bk. 13, ch. 6,

http://www.ccel.org/j/josephus/works/ant-13.htm; Simo Parpola,

"National and Ethnic Identity in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and

Assyrian Identity in the Post-Empire Times", Journal of Assyrian

Academic Studies 18, 2 (2004): 16�17; Simo Parpola, "Assyrians

after Assyria", Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies 12, 2

(2000): 1�13; R.N. Frye, "A Postscript to My Article [Assyria and

Syria: Synonyms]", Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies 11

(1997): 35�36; R.N. Frye, "Assyria and Syria: Synonyms", Journal

of the Near East Society 51 (1992): 281�85;

Michael G. Morony, Iraq after the Muslim Conquest

(Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1984), 336, 345;

J.G. Browne, "The Assyrians", Journal of the Royal Society of

Arts 85 (1937)

-

^

Smith, Sidney (1925).

"Early History of Assyria to 1000 B.C.". "The disappearance of

the Assyrian people will always remain a unique and striking

phenomenon in ancient history. Other, similar kingdoms and empires

have indeed passed away but the people have lived on... No other

land seems to have been sacked and pillaged so completely as was

Assyria."

-

^ Saggs,

The Might That Was Assyria, pp. 290, �The destruction of the

Assyrian empire did not wipe out its population. They were

predominantly peasant farmers, and since Assyria contains some of

the best wheat land in the Near East, descendants of the Assyrian

peasants would, as opportunity permitted, build new villages over

the old cities and carry on with agricultural life, remembering

traditions of the former cities. After seven or eight centuries and

various vicissitudes, these people became Christians.�

-

^

Biggs, Robert (2005).

"My Career in Assyriology and Near Eastern Archaeology" (PDF).

Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies 19 (1).

pp. 10, �Especially in view of the very early establishment of

Christianity in Assyria and its continuity to the present and the

continuity of the population, I think there is every likelihood that

ancient Assyrians are among the ancestors of modern Assyrians of the

area.�

-

^

Parpola, National and Ethnic Identity in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and

Assyrian Identity in Post-Empire Times, pp. 22

-

^

Frye, Richard N. (1992).

"Assyria and Syria: Synonyms". PhD., Harvard University.

Journal of Near Eastern Studies. "The ancient Greek historian,

Herodotus, wrote that the Greeks called the Assyrians, by the name

Syrian, dropping the A. And that's the first instance we know of, of

the distinction in the name, of the same people. Then the Romans,

when they conquered the western part of the former Assyrian Empire,

they gave the name Syria, to the province, they created, which is

today Damascus and Aleppo. So, that is the distinction between

Syria, and Assyria. They are the same people, of course. And the

ancient Assyrian empire, was the first real, empire in history. What

do I mean, it had many different peoples included in the empire, all

speaking Aramaic, and becoming what may be called, "Assyrian

citizens." That was the first time in history, that we have this.

For example, Elamite musicians, were brought to Nineveh, and they

were 'made Assyrians' which means, that Assyria, was more than a

small country, it was the empire, the whole Fertile Crescent."

- ^

a

b

Frye, R. N. (October 1992).

"Assyria and Syria: Synonyms" (PDF).

Journal of Near Eastern Studies 51 (4): 281�285.

doi:10.1086/373570.

pp. 281-285

-

^

"Eastern Churches",

Catholic Encyclopedia, see "Eastern Syrians" and "Western

Syrians" respectively. Modern terminology within the group is

Western Assyrians and Eastern Assyrians respectively, while those

who reject the Assyrian identity opt for

Syriacs rather than Assyrian.

-

^

http://www.aina.org/ata/20070218144107.htm

-

^

Rollinger, Robert (2006).

"The terms "Assyria" and "Syria" again" (PDF).

Journal of Near Eastern Studies 65 (4): 283�287.

doi:10.1086/511103.

-

^

Parpola, National and Ethnic Identity in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and

Assyrian Identity in Post-Empire Times, pp. 16

-

^

Festschrift Philologica Constantino Tsereteli Dicta, ed. Silvio

Zaorani (Turin, 1993), pp. 106-107

-

^

Rudolf Macuch, Geschichte der sp�t- und neusyrischen Literatur,

New York: de Gruyter, 1976.

-

^

Tsereteli, Sovremennyj assirijskij jazyk, Moscow: Nauka,

1964.

-

^

Tekoglu, R. & Lemaire, A. (2000). La bilingue royale

louvito-ph�nicienne de �inek�y. Comptes rendus de l�Acad�mie des

inscriptions, et belleslettres, ann�e 2000, 960-1006.

-

^

Rollinger, Robert (2006).

"The terms "Assyria" and "Syria" again" (PDF).

Journal of Near Eastern Studies 65 (4): 284�287.

-

^

http://www.aina.org/articles/chicago.pdf

-

^

The Assyrian New Year

-

^

Chamberlain, AF. "Notes on Some Aspects of the Folk-Psychology of

Night". American Journal of Psychology, 1908 - JSTOR.

-

^

Gansell, AR. FROM MESOPOTAMIA TO MODERN SYRIA: ETHNOARCHAEOLOGICAL

PERSPECTIVES ON FEMALE ADORNMENT DURING RITES. Ancient Near Eastern

Art in Context. 2007 - Brill Academic Publishers.

-

^

"Microsoft Word - PeshittaNewTestament.doc" (PDF).

Retrieved 2008-11-16.[dead

link]

-

^

Bae, C. Aramaic as a Lingua Franca During the Persian Empire

(538-333 BCE). Journal of Universal Language. March 2004, 1-20.

-

^

Aramaic Documents of the Fifth Century B. C. by G. R. Driver

-

^

Akkadian Words in Modern Assyrian

-

^ Kaufman, Stephen A. (1974),The Akkadian influences on

Aramaic. University of Chicago Press

-

^

The British Survey, By British Society for International

Understanding, 1968, page 3

-

^

A Statue from Syria with Assyrian and Aramaic Inscriptions

-

^

[10]

-

^

[J. Martin Bailey, Betty Jane Bailey, Who Are the Christians in the

Middle East? p. 163: "more than two thirds" out of "nearly a

million" Christians in Iraq.]

-

^

Adherents.com

-

^

The Date of Easter. Article from

United States Naval Observatory (March 27, 2007).

- ^

a

b

Dr. Joel J. Elias, Emeritus, University of California, The Genetics

of Modern Assyrians and their Relationship to Other People of the

Middle East

-

^

M.T. Akbari, Sunder S. Papiha, D.F. Roberts, and Daryoush D. Farhud,

��Genetic Differentiation among Iranian Christian Communities,��

American Journal of Human Genetics 38 (1986): 84�98

-

^

Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza, Paolo Menozzi, Alberto Piazza,

The History and Geography of Human Genes, p. 243

[11]

-

^

Banoei et al., Human Biology. February 2008, v. 80, no, I, pp.

73-81., "Variation of DAT1 VNTR alleles and genotypes among old

ethnic groups in Mesopotamia to the Oxus region""The

relationship probability was lowest between Assyrians and other

communities.

Endogamy was found to be high for this population through

determination of the heterogeneity coefficient (+0,6867), Our study

supports earlier findings indicating the relatively closed nature of

the Assyrian community as a whole, which as a result of their

religious and cultural traditions, have had little intermixture with

other populations."

-

^

Yepiskoposian et al., Iran and the Caucasus, Volume 10, Number 2,

2006 , pp. 191-208(18), "Genetic Testing of Language Replacement

Hypothesis in Southwest Asia"

Further reading

- Aphram I Barsoum, Patriarch (1943).

The Scattered Pearls.

- Benjamin, Yoab (PDF).

Assyrians in Middle America: A Historical and Demographic Study

of the Chicago Assyrian Community. 10.

Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies.

- BetGivargis-McDaniel, Maegan (2007).

Assyrians of New Britain.

Arcadia Publishing.

ISBN 0738550124.

OCLC 156908771.

- Brock, Sebastian (9 September 2002).

The Hidden Pearl: The Aramaic Heritage. Trans World Film.

ISBN 1-931956-99-5.

http://www.gorgiaspress.com/BOOKSHOP/pc-151-25-brock-et-al-sebastian-the-hidden-pearl-the-aramaic-heritage.aspx.

-

De Courtis, Sėbastien (2004). The Forgotten Genocide: Eastern

Christians, the Last Arameans (1st Gorgias Press ed.).

Piscataway, New Jersey : Gorgias Press.

ISBN 1593330774

9781593330774.

- Donabed, Sargon; Donabed, Ninos

(2006). Assyrians of Eastern Massachusetts.

Arcadia Publishing.

ISBN 0738544809.

OCLC 70184669.

-

Ephrem I Barsaum, Ignatius (2006) (in Swedish). De spridda

p�rlorna - En historia om syriansk litteratur och vetenskap.

Sweden: Anastasis Media AB.

ISBN 9197575143.

- Gaunt, David; Jan Bet̲-Şawoce, Racho

Donef (2006). Massacres, resistance, protectors: Muslim-Christian

relations in Eastern Anatolia during World War I. Gorgias Press

LLC.

ISBN 1593333013.

OCLC 85766950.

- Henrich, Joseph; Henrich, Natalie

(May 2007).

Why Humans Cooperate: A Cultural and Evolutionary Explanation.

Oxford University Press.

ISBN 0195314239.

- Hollerweger, Hans (1999) (in

English, German, Turkish). Tur Abdin: A Homeland of Ancient

Syro-Aramaean Culture. �sterreich.

ISBN 3-9501039-0-2.

-

MacDonald, Kevin (2004-07-29).

Socialization for Ingroup Identity among Assyrians in the United

States.

-

Parpola, Simo (2004).

"National and Ethnic Identity in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and

Assyrian Identity in Post-Empire Times" (PDF).

Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies 18 (2).

-

Taylor, David; Brock, Sebastian (9 September 2002). Vol. I: The

Ancient Aramaic Heritage. Trans World Film.

-

Taylor, David; Brock, Sebastian (9 September 2002). Vol. II: The

Heirs of the Ancient Aramaic Heritage. Trans World Film.

-

Taylor, David; Brock, Sebastian (9 September 2002). Vol. III: At

the Turn of the Third Millennium; The Syrian Orthodox Witness.

Trans World Film.

External links

|

[hide]v

�

d

�

eAssyrian/Chaldean/Syriac

communities around the world |

| |

|

Homeland |

|

|

| |

|

Diaspora |

|

Western world

|

|

| |

|

Former Soviet Union

|

|

|

|

|

[hide]v

�

d

�

eEastern

and

Oriental Orthodox Christian Ethnic Groups |

| |

| Majority |

|

European

|

|

| |

|

Afro-Asiatic

|

|

| |

|

Altaic

|

|

| |

|

Uralic

|

|

| |

|

Chukotko-Kamchatkan

|

|

|

| |

| Minority |

|

|

|

|

|